Author: Jesse McCarthy-Price

Published: March 26, 2018

There’s that overused John Lennon quote that says, “Life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans”.

Geoffrey ‘Speed’ Smith is a man of few words, but when I meet with him to chat a little about his life and career, it’s that clichéd quote that comes to mind. Smith was supposed to be a farmer, until fate intervened, steering him on a rollercoaster course through a 30-year long career as an artist.

But in a mass produced modern world, Smith feels unsure of whether there is a future in his artform, or any artform at all. “It’s just the reality with all crafts today—everyone is struggling to be viable. You are a point where you just think, ‘What am I doing?’.”

Raised on a farm in Grass Patch, it was a trip to Penong that altered his life forever. The dusty South Australian town was much like every other rural community around him, except for one small fact. It was harbouring a secret. Just 21km down a dirt road were world class waves.

Suddenly life as he knew it lost its allure. Was he ever tempted to return to a life on the farm? “Not once I started surfing, nah” he laughs. He would return to work seasonally to make money, before he’d hit the road, bound for Cactus, spending months at a time housed in shanties of old caravans, tarpaulins and swags.

“There were people from America, South Africa, all these people on the road, surfing. I went down there and I met that crew and of course, all the drugs and the quality of the gunja and acid. The world class waves, I was committed to riding those wave as best as I could. I thought, ‘Man, there’s more to life than Grass Patch, that’s for sure’.”

It was around this time, Speed started painting. Always drawing as a kid, he decided to try his luck at painting surfboards. He was inspired by the album art of bands like Yes designed by artists like Roger Dean, popular during the early ‘70s. Teaming up with his mate, the now renowned boardshaper Paul Gravelle, Smith’s future once again took a turn, propelling him into the art world.

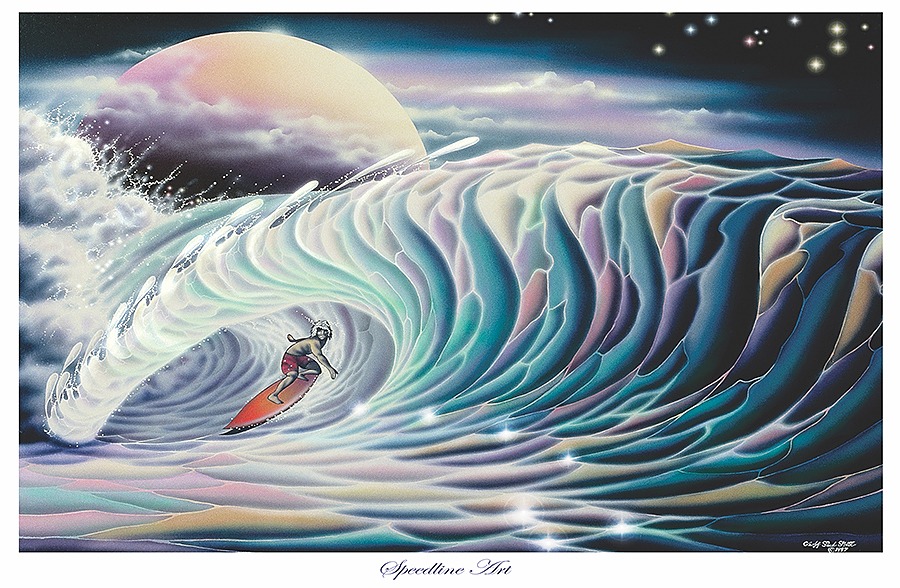

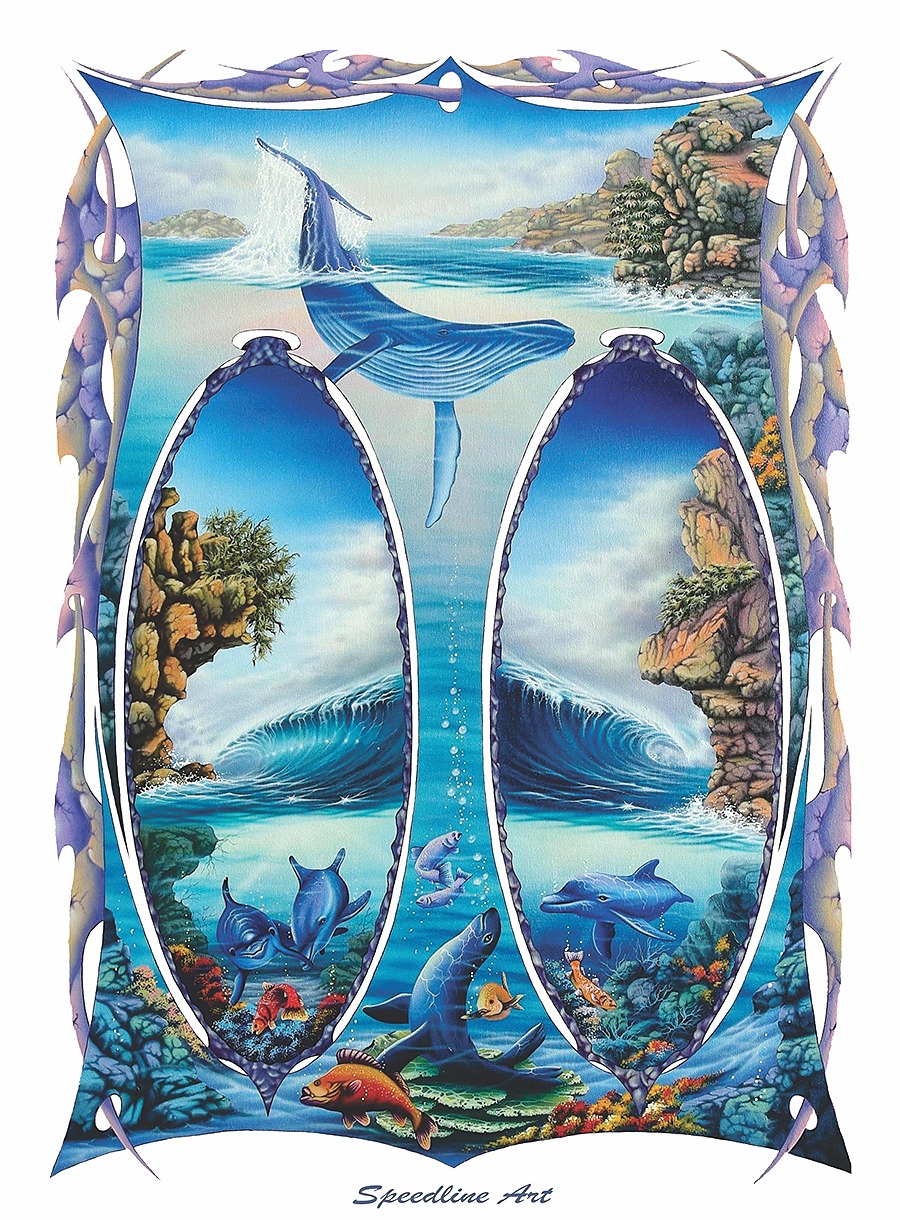

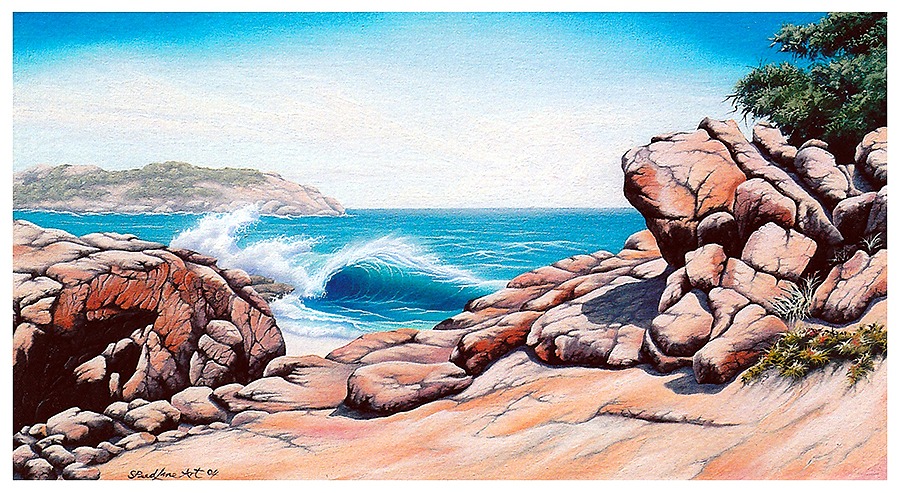

Rich in theme, Smith’s work turns his favourite places into literal fantasylands. Esperance, Cactus, the Bluff become playgrounds full of spirit and magic. It takes masterful use of acrylics, oils and airbrush inks to have such an ethereal effect. Humanity and all its ugliness is absolved from his compositions, and despite the hours of labour that goes into each piece, there is no trace of the clumsiness of human exertion. Smith creates art of divinity and purity.

“I’m completely self taught,” he says. “I got magazines on how to use the airbrush and picked up skills. I’ve bought a lot of books and studied heaps of different artists, particularly in fantasy art—artists like Rodney Matthews who did those Uriah Heep album covers and all those bands—I really liked all that work.”

By the 1990s, Smith had hit the road, touring his artwork and donning his best salesman smile to promote his creations. “I thought, ‘I’m going to get really stuck into this and see where I can take it’. I’d sell cards, posters—I was getting by financially. I used to be able to stay afloat and surf, and I’d do a little bit of [limestone] stonework in between.” If you were in Esperance by the late 90s, you knew Smith’s art by sight: Speedline Art was everywhere.

Smith is not the kind of person who would ever desire fame. Every inch of his being tells you that. But there’s a sort of vindication that is central to every artist’s creative process. When I ask him what it is he wants his art to achieve, he shrugs uncomfortably and we both say with the same uncertainty, “Survival?”

The reality is, Smith’s art form is dying. The modern surfer isn’t interested in sturdy boards like Paul Gravelle’s. Worshipped like gods at the altar of the WSL circus, pro surfers serve as brand ambassadors to a small handful of ‘performance-based’ brands. Popularity for these machine-shaped boards skyrockets, leaving the rest of the industry in the dust. And with high price tags on them, there’s little budget or desire left for artwork. “There are so few of us,” Smith says. “A few blokes are still plugging away, but they’re not making much money. They’re making beautifully crafted surfboards, but they’ve gotta compete with machines.”

For financial viability, Smith says he would have to at least consider a move to Margaret River or Byron Bay, a suggestion about as good as a fin to the crotch. A move to the Australian capitals of commercial surfing probably isn’t on the cards for a man who has spent his whole life ducking crowds.

And so, the future is uncertain, but that’s nothing new for Speed Smith. Fate has been kind to him—few get to touch the ocean so thoroughly, live so lightly. If the less-travelled road his life has ambled along is anything to go by, the next chapter may be foggy but it sure can still be bright.